Gustav Gurschner

Gustav Gurschner | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Gurschner painted by Jules Koehler, by 1900 | |

| Born | 28 September 1873 Mühldorf, Germany |

| Died | 2 August 1970 (aged 96) Vienna, Austria |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Education | Kunstgewerbeschule, Vienna |

| Known for | Sculpture, Decorative arts |

| Movement | Vienna Secession, Hagenbund |

Gustav Gurschner (28 September 1873[1]–2 August 1970) was an Austrian sculptor whose works ranged from monuments to decorative everyday objects like lamps and ashtrays in the Art Nouveau style. He was the husband of the writer Alice Pollak.

Education and career

[edit]Gurschner was born in Mühldorf, in Bavaria, the son of a surveyor. He was trained at the technical school for wood sculpture in Bolzano, then studied under August Kühne and Otto König at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts) in Vienna. During this time, he supported himself by teaching drawing. He also sold his first commission, a bust of the actor Wilhelm Knaak. The bust was included at an exhibition at the Vienna Künstlerhaus in 1896; on opening day, artists stood next to their works while Kaiser Franz Joseph passed in review. Amid the other artists, the twenty-two-years-old, clean-shaven Gurschner looked so young that the Kaiser asked him why he was there instead of his father, then expressed astonishment when he was told that Gurschner was in fact the maker of the bust. The notice of the Kaiser was a signal event in Gurshner's rise as an artist.[2]

Gurschner completed compulsory military service with the Kaiserjäger in Innsbruck from 1895 to 1896, then lived briefly in Munich.[3]

After his marriage to Alice Pollak in 1897, the couple moved to Paris, where Gurschner studied under Ville Vallgren[5][6] and was also influenced by Jean Dampt, Alexandre Charpentier, and Henry Nocq, especially their "artistic redesign of everyday objects. That's what they wanted," Gurschner later recalled, "to elevate these things to the rank of small sculptural works of art." What fascinated him most was the artistic design of the household electric lamp, a new technology at the time.[3][7]

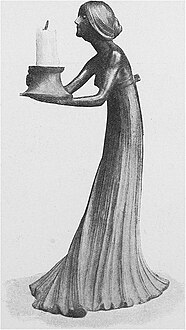

In 1898, he exhibited three works at the Salon du Champ-de-Mars, a candlestick, a hammer, and a lamp. The Musée Galliera acquired a door knocker designed by Gurschner, now in the collection of the Petit Palais.[3]

His success in Paris drew the attention of artists in Vienna, who invited him to participate in the inaugural exposition of the Vienna Secession in 1898, where Gurschner exhibited a bronze lamp and a bronze chandelier (catalog numbers 15 and 16).[8][9]

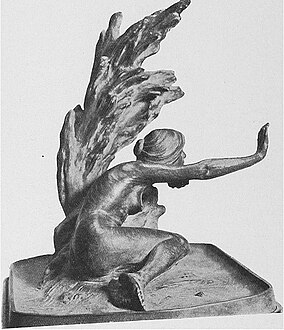

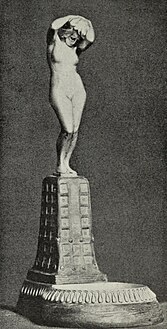

Later in 1898, Gurschner and Alice moved from Paris back to Vienna. Breaking away from the Secession, Gurschner became part of the Hagenbund, a group of like-minded Austrian artists. In the first Hagenbund exhibition of January, 1902, he showed not smaller, utilitarian works, but a silver statuette, Schmerz (Pain), and a ten feet tall marble sculpture, Liebe und Neid (Love and Envy), which was installed on the grounds of the Villa Vogel in Stockerau (catalog numbers 16 and 56).[10][11]

Turn-of-the-century Vienna "offered ideal conditions for a strong talent, which the young artist knew how to exploit with characteristic élan. In addition to an abundance of arts and crafts objects of all kinds, a large number of figural sculptures were created in his studio, as well as portrait busts, medals, and plaques."[10]

Outside Austria, he became best known for household objects such as those imported by New York galleries. In 1900, The Artist published a copiously illustrated article, "Gustav Gurschner and His Work",[12] and in 1901 the New York Times declared him a leader of the Art Nouveau movement second only to Vallgren.[13]

As his career progressed in Austria, Gurschner excelled at sculptural portraiture, especially in bas-relief. His subjects included artists, actors, politicians, military officers, industrialists, members of the nobility, and the imperial family.[14]

Sportsman and soldier

[edit]

Gurschner was also an early automobile enthusiast and "one of Austria's first sports motorists."[10] He designed and executed prizes for the Henry Edmond,[14] Gordon Bennet, and Herkomer automobile races,[15] and also for the Motor Yacht Club of Germany and Austria[16] and the Imperial-Royal flying club.[17]

Gurschner "recognized the usefulness of the new invention for the army and set about implementing...the establishment of an automobile corps." His efforts eventually "led to the founding of the K.k. Freiwillige-Automobilkorps [Imperial-Royal Volunteer Automobile Corps] and the K.k. Freiwillige-Motorfahrerkorps [Imperial-Royal Motor Driver Corps], with the latter under command of Oberleutnant [first lieutenant] Gustav Gurschner," who drove in a processsion before the Kaiser in June, 1912. During the parade, a fierce thunderstorm erupted, but the aged Kaiser, standing on a balcony in pouring rain, wearing a bicorne hat and a cloak draped over his shoulders, never budged. The image of the stalwart emperor became indelible in Gurschner's memory, and it was this pose he would depict two decades later when he was commissioned to sculpt a life-size monument of Franz Joseph in Vienna.[18]

In June, 1914, Gurschner initiated a campaign to recruit a volunteer army to support the recently installed Albanian monarch William, Prince of Albania, whom he knew personally, against insurgent troops in Durrës. (Gurschner also designed uniforms of the Albanian militia and military decorations for the prince.) Two thousand Austrian volunteers were recruited in two days, but the effort exacerbated tensions between Austria and Italy, and Austrian authorities closed the recruiting office. In July, only 150 Austrian volunteers arrived in Albania, led by Gurschner. With the outbreak of the First World War, political chaos engulfed Albania, and Prince Wilhelm left the country in September 1914.[14][19][20]

The military adventurer Duncan Heaton-Armstrong recalled that

Gurschner himself very nearly got into trouble with the Austrian authorities for trying to enlist men for a foreign power and as far as I remember he was, or just escaped, being arrested for this offense. About the middle of the month [July, 1914] he appeared on the scene at Durazzo [Durrës], where he remained for a few weeks. He got heartily sick of the place and returned to Vienna, there to design an Albanian war medal; this however was never finished, as the Austro-Serbian war broke out and the artist had to join the army as a reserve officer.[21]

An undated portrait in the Museum of Military History in Vienna depicts Gerschner in uniform beside an automobile and gives him the rank of Hauptmann Gerschner.[22]

During World War I, Gurshner turned his focus to medals and badges, such as those issued to individuals and to army units, and later, monuments to the fallen.[18]

In the U.S., a 1915 Christmas article on gifts in the Fine Arts Journal reflected on the impact of the war on the decorative arts, and mistakenly reported Gurschner's death in battle:

There is a little of the somber in the story of many of these lovely things, for they are the works of French, German and Austrian artists, many of whom are now turned from elegant creation to the most hideous of destruction; and some of whom have perhaps been destroyed and all their art and cunning wasted. Such is the story of the productions bearing the signature of Gurschner, the clever young Viennese whose heroic works are well known to his countrymen, having won him fame and recognition among all the courts of Europe. Enjoying royal favor, he was made commander of the first motorcycle corps of the Austrian army, which was fitted out at the command of the Emperor. The death of this gifted man in battle, as recently reported, adds a tragic interest to these examples of his handiwork.[23]

After World War I

[edit]

The years after the war, with a defeated Austria in shambles, saw a reversal of fortune. In an interview published in 1930, Gurschner looked back to his early days: "I wanted to create in complete freedom, and I could afford to, because I was a rich man at the time. Then, of course, with the war and the post-war period, came bitter years for us artists. Well, things still haven't turned out very rosy."[24]

An interview and article from 1966, when Gurschner was 93, included a list of his most important works, with the last work on the list dated 1931.[25] Although the article is titled "Leben und Werk des Bildhauers Gustav Gurschner" (Life and Work of the Sculptor Gustav Gusrchner), nothing is said of his circumstances in the four decades after 1931, except for the fact that Gurscher in 1966 received the interviewer, Franz Windisch-Graetz, at a studio in Vienna's seventh district "full to bursting" with photographs, documents, memorabilia, and artworks, including a veritable "portrait gallery of Austrian and foreign personalities of the first half of our century...Something of the former vastness of old Austria and of the central importance of Vienna at that time can still be felt in this studio," wrote Windisch-Graetz.[26]

Gurschner's wife, Alice, who was Jewish and a Catholic convert, continued to publish works until at least 1938, the date of her novel Drei Häuser: Roman aus Alt-Österreich. How her Jewish origin may have impacted their lives under the Nazis has not yet been documented, but it is reported that she was taken away by the SS only to be brought home by Gurschner under unknown circumstances. She died March 26, 1944, in Vienna. Gurschner survived her by more than twenty-six years, dying August 2, 1970.

Personal life

[edit]Gurschner married the writer Alice Pollak (1869-1944) on May 5, 1897.[27] Alice came from an upper-class Jewish family, and her marriage to the Catholic Gurschner was not welcomed by her parents. After her father died in 1905, Alice converted to Catholicism. Over a fifty-year career she wrote novels, poetry, and works for the stage, as well as reviews and articles for newspapers and journals, from 1890 using the pseudonym Paul Althof.

The Gurschners had three children. Their son Harald (born in Vienna October 6, 1898 - died January 16, 1964) founded a film production company with Olaf Fjord in 1920 and briefly worked as a director; later he followed his father's passion for motorsports and devoted himself to motorcycling. Their daughter Eva Martina married the artist Theodor Zeller (1900-1986). Gurschner's second son was named Gerhart-Dietrich.

In a 1904 interview, Alice looked back on their time in Paris, essentially an extended honeymoon.

"That was a wonderful time, unforgettable. I married very young and we were both drawn to art. We lived in a hotel in Paris, ate badly and lived without comforts, breathing la vie Bohème. That's what we wanted. Artists' cafes and ateliers were our places of residence and the whole of Montmartre surrounded us. We had money and didn't have to go hungry, [but until] the fifteenth of each month we were naked, without a sous, and those were always cheerful times, when we were as destitute as the others. Only then did the real Verlaine mood come, and we were full-blooded comrades of the Bohemians."[28]

Alice expressed unconventional views on sexual jealousy. "The most ridiculous women are those who demand purity from men...I grant the man all his rights, he doesn't have to be pure, he doesn't have to be faithful, to put it more commonly. It's a matter of temperament. A clever woman should never be jealous when another woman captivates her husband's senses for a short while. With such views, a lot of misfortune would be eliminated from the world."[28]

As to her role in the marriage of two artists, she said, "My husband is a sculptor, which inspires me mightily, he designs clothes for me and jewelry...I have completely immersed myself in his art, I am able to be his avenger and helper, I take care of all his business agendas, and I am happy with every new work, I see a part of myself in every creation...He may have less interest in my art," she said, and in the same interview, Gurschner admitted that he read little of his wife's work.[28]

The young couple's home in Vienna had numerous "rooms, sumptuous and ornate," with "no shortage of magnificent works of art, paintings by modern masters and creations of the owner...the large dining room, which presents as a Norwegian farmhouse parlor, is also magnificent; from Tyrolean castles come the old pictures on the walls" and "the rich pewter jugs on racks. From the hall, a corridor leads to Gurschner's studio...I admire his renowned small works of art, the vases and plates, the jugs, goblets, sculptures, candlesticks and lamps, these soft, supple women's bodies he captures in metal more beautifully than almost anyone else."[28]

Gurschner's brother Emil (1886–1938) was also a sculptor; Gustav and Emil's nephew Herbert Gurschner (1901–1975) was a painter and worked in London.[29]

In Museums and public spaces

[edit]

In the United States, Gurschner's work can be found in the Wolfsonian-FIU,[30] the American Numismatic Society collection of medals,[31][32] the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum,[33] and the Corning Museum of Glass;[34] in Paris, at the Petit Palais;[4] in Innsbruck, at the Tiroler Kaiserjägermuseum;[35] in Vienna, at the Vienna Museum,[36] at the Museum of Applied Art (MAK) and at the Museum of Military History, which also holds a portrait of Gurschner in uniform, painted by Hermann Hanatschek.[22]

Gurschner's surviving works of sculpture include the four monumental marble figures depicting armed men that adorn the facade of the Jägerndorf Schützenhaus (Shooting Clubhouse), now the Středisko volného času (Leisure Center), in Krnov, Czech Republic (by 1915);[14] in Stockerau, Liebe und Neid (1902), on the grounds of the Villa Vogel, and a funerary monument for the Vogel family in the Stockerau cemetery;[37] in Vienna, two bronze medallions dated 1926 on the Karczag family monument in Hietzing Cemetery, a life-size sculpture of Isac Leon Eskenasi in Döbling Cemetery (1926), and the bronze Monument to the Fallen of the Dragoon Regiment Prince of Windisch-Graetz No. 14 at the Augustinian Church (1931);[38] in Salzburg, commemorative plaques for fallen officers of the Austro-Hungarian artillery (1924) and the fallen of the engineering academies (1927) in the Kollegienkirche;[14] in Moltën, a marble relief of mother and infant at the gravesite of Gurschner's mother, Aloisia (d. 1921), at the St.-Anna-Kirche.[39]

Gallery: electric lamps, c. 1900-1915

[edit]-

Nautilus lamp

-

Abandoned, electric lamp

-

Electric lamp

-

Wall-mounted light fixture

-

Fairy lamp, bronze and shell

-

Table lamp, bronze

-

Table lamp, bronze

-

Table lamp, bronze

-

Serpentaria blossoms, electric light fitting

Gallery: decorative household objects, c. 1900-1915

[edit]-

Truth, bronze and mirror

-

Palm pot, bronze

-

Seal

-

Pen-tray

-

Will-o-the-wisp cigar lighter

-

Ashtray

-

Ashtray

-

Bronze candlestick

-

Bronze double candlestick

-

Cabinet with bronze fittings

-

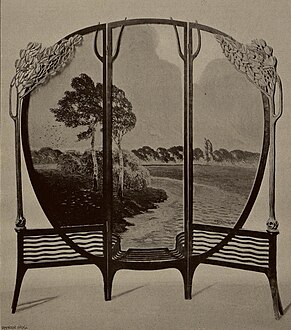

Bronze frame for painted screen

-

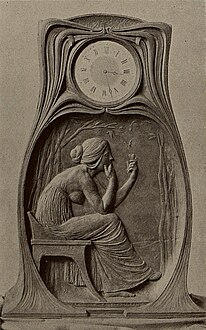

bronze clock

-

Door-plate

-

Three brooches

-

Green marble book ends with green bronze busts

References

[edit]- ^ Thieme and Becker (1922).

- ^ Windisch-Graetz (1966), pp. 34-35.

- ^ a b c Windisch-Graetz (1966), p. 35.

- ^ a b "Heurtoir". www.parismuseescollections.paris.fr. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ F——d (1900), p. 80.

- ^ "L'ART NOUVEAU.; Sculptures in Little for the Home, the Office, and Public Rooms". New York Times. 1901-05-19. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ In 1897, Gurschner may also have had contact with Fritz von Uhde. He painted an oil on canvas study of Uhde's Christi Himmelfahrt (Ascension of Christ); both works are dated 1897 and are reproduced side by side on pages 192-193 in Rosenhagen, Hans. Uhde, des Meisters Gemälde in 285 Abbildungen, Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-anstalt, 1908. It is an atypical work in Gurschner's known oeuvre.

- ^ "Vienna Secession | catalogues | 1890-1900". www.theviennasecession.com. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ Windisch-Graetz (1966), p. 36.

- ^ a b c Windisch-Graetz (1966), p. 37.

- ^ "Katalog der Eröffnungsausstellung: Künstlerbund Hagen ; Januar 1902". digitale-bibliothek.belvedere.at. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ F——d., W. (1900).

- ^ "L'ART NOUVEAU.; Sculptures in Little for the Home, the Office, and Public Rooms". New York Times. 1901-05-19. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

Valgrin [sic] of Paris has led in this branch of art, and Gurschner of Vienna is a good second.

- ^ a b c d e Windisch-Graetz (1966), p. 39.

- ^ "Designers..." (1909), pp. 139-140, which gives Gurschner's address as Lindengasse 7, Vienna VII.

- ^ "A Gustav Gurschner Bronze Yachting Trophy". liveauctioneers.com. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- ^ Windisch-Graetz (1966), p. 38.

- ^ a b Windisch-Graetz (1966), pp. 37-38.

- ^ Löhr (2010), pp. 222ff.

- ^ "Die neueste Dummheit..." (1914).

- ^ Heaton-Armstrong (2005), p. 138.

- ^ a b "Ölgemälde-Portrait Hauptmann Gustav Gurschner (1873-1970)". www.hgm.at. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ Richards (1915), p. 537-538.

- ^ Strauß-Gutmann (1930), p. 8.

- ^ Windisch-Graetz (1966), pp. 38-39, lists, describes, and includes a photograph of Gurschner's Monument to the Fallen of the Dragoon Regiment Prince of Windisch-Graetz No. 14 at the Augustinian Church (1931).

- ^ Windisch-Graetz (1966), pp. 34.

- ^ Pataky, Sophie. Lexikon deutscher Frauen der Feder, vol. 1, Berlin: Verlag Carl Pataky, 1898, p. 296.

- ^ a b c d Deutsch-German (1904), p. 4.

- ^ "Herbert Gurschner". www.kovacek.at. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ "The Wolfsonian—Gustav Gurschner". digital.wolfsonian.org. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ "Artist: Gustav Gurschner". numismatics.org. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ Heath (2006).

- ^ "Gustav Gurschner | People | Collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum". collection.cooperhewitt.org. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ "table lamp". glasscollection.cmog.org. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ Two portraits dated 1896, Erzherzog Ferdinand Karl and Oberst von Steine, according to Windisch-Graetz (1966), p. 39.

- ^ "Auf die Hilfe der Wiener für die Bedürftigen, Verwaisten und Invaliden, ausgegeben vom Schwarzgelben Kreuz und dem Invalidenfond". sammlung.wienmuseum.at. Retrieved March 25, 2024.

- ^ Windisch-Graetz (1966), pp. 37 and 39, which also cites a portrait of Elise Vogel made by Gurscher in 1930.

- ^ Windisch-Graetz (1966), pp. 38-39, describes and includes a photograph of the monument.

- ^ The gravestone is inscribed "Ruhestätte der Gotigefälligen Frau und Besten Mutter" (Resting place of the godly woman and best mother).

Bibliography

[edit]- Abels, Dr. Ludwig, editor. Das Interieur: Wiener Monatshefte für Angewandte Kunst, Vienna: Kunstverlag Anton Schroll & Co., volumes for 1900, 1901, 1902.

- "Designers of Jewelry, Enamels, Metal and Leather Work," The Studio Year-Book of Decorative Art, London: Offices of The Studio, 1909, pp. 139-140.

- Deutsch-German, Alfred. "Wiener Porträts XCVII: Paul Althof", Neues Wiener Journal, March 13, 1904, p. 4.

- "Die neueste Dummheit der auswärtigen Politik Österreichs", Arbeiterwille, Graz, July 1, 1914, p. 2.

- F——d., W. "Gustav Gurschner and His Work", The Artist: An Illustrated Monthly Record of Arts, Crafts and Industries (American Edition), vol. 28, no. 246, 1900, pp. 73–83.

- "Studio-Talk: Vienna", The Studio", vol. 24, 1901-1902, pp. 139-142.

- Heath, Sebastian, et. al. "Acquisitions for 2005 in the American Numismatic Society Collection", American Journal of Numismatics, 2006, Vol. 18, p. 189, item numbers 82 and 84.

- Heaton-Armstrong, Duncan. The Six Month Kingdom: Albania 1914, Bloomsbury, 2005.

- Holme, Charles, editor. The Art-Revival in Austria, London: Offices of The Studio, 1906.

- Löhr, Hanns Christian. Die Gründung Albaniens: Wilhelm zu Wied und die Balkan-Diplomatie der Grossmächte, 1912–1914, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2010, pp. 222ff.

- Richards, Agnes Gertrude. Artistic Bits of Bronze and Glass, Fine Arts Journal, Vol. 33, No. 6 (December, 1915), pp. 535-543.

- Strauß-Gutmann, Hilda. "Besuch bei Gustav Gurschner", Neues Wiener Journal, April 30, 1930, pp. 8-9.

- Thieme, Ulrich and Becker, Felix, editors. "Gurschner, Gustav" in Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, vol. 15, p. 349, Leipzig: Verlag von E.A. Seemann, 1922.

- Windisch-Graetz, Franz. "Leben und Werk des Bildhauers Gustav Gurschner", Alte und moderne Kunst, Vienna, vol. XI, no. 87, 1966, pp. 34–39.

External links

[edit]- Portrait of Gustav Gurschner in uniform, oil on canvas by Hermann Hanatschek, in the collection of the Museum of Military History, Vienna.

- Photograph of Alice Gurschner c. 1910.